Two months ago we, at nanit.com, had to make a difficult choice. We already knew our infrastructure is going to heavily rely on Docker, but we still had to figure out what tool we would use to orchestrate our containers.

Orchestrating is a big word and might sound vague to someone which has not dealt with Docker containers before, so let’s clarify what it exactly means in the Docker world.

The Evolution of Operations

So why do we need orchestration? What does an orchestrator even do? Is it a new concept that rose with the evolution Docker has brought into our lives or was it always there and just became a necessity now days?

The answer to all of those questions hides in the inherent and deep difference Docker introduced to the way our infrastructure looks and behaves.

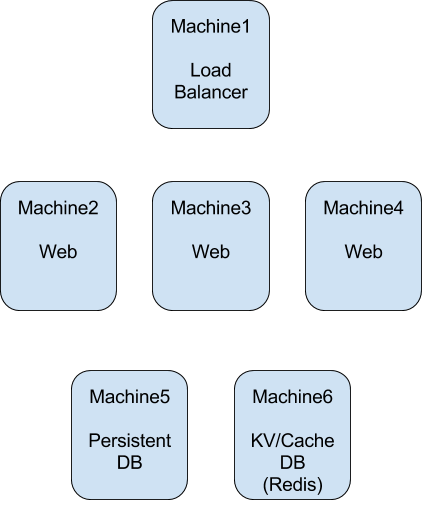

On the days before Docker, we had either physical or virtual machines. Each machine (physical or virtual) was usually responsible for a single function. For example, let’s look at a typical infrastructure of a web site:

What we see here is a frontend load balancer with 3 web servers behind it. The servers communicate with a persistent DB (mySQL, Postgres etc…) and a KV storage. Each of the machines here is responsible for a single, well defined function. Each of them has an IP address and a port which allow us to communicate with the service running on them. Another important thing to notice is the size of each machine: A KV DB might need a lot of memory and small amount of CPU, while our web server might be more CPU intensive. We set the resources on each machine to allow it to serve its function in a fast and consistent manner.

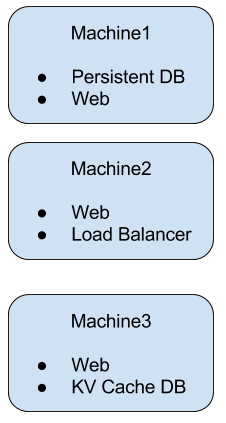

The same website in the Docker era might look like this:

We still have the same components but now they are arranged differently. Two or even more, totally different containers, may live together on the same machine. A container might live in Machine1 and be moved to Machine2 later on. The concept of a machine or a host does not exist anymore. We don’t have a machine for a Database and a machine for a Load Balancer. We have a pool of resources (memory/cpu/network) which is the sum of all the resources of the machines on our cluster. This introduces a few interesting changes to the way we manage our infrastructure:

-

Service Discovery: If we don’t have machines anymore, how can we identify services? How can we tell our Web container to connect to the DB container which may live on the same machine, on another machine and move between machines all the time? How can we point our DNS record of www.nanit.com to the Load Balancer if we don’t know on which machine it currently lives in?

-

High Availability: How can we make sure our services are always up and retain a certain capacity, for example: we want at least 3 web servers running within our cluster.

-

Resources Management: How can we make sure our cluster’s pool of resources is being used in an optimized manner? How can we make sure that the machine a container is going to be spawned in, has enough resources to run the service effectively? We have to make sure we don’t over-load a single machine and that we don’t neglect another machine.

-

Ports Management: What happens if two containers require the same port to be opened on the host? For example: The Web Server and the Load Balancer both need port 80. We need to make sure we don’t run them both on the same machine. Or, maybe, we can find another solution, that will allow them to co-exist on the same machine, even though they need the same port?

I want to briefly go over each of these topics and figure out what are the Docker influences and available solutions.

Service Discovery

Service discovery is a problem which had solutions long before Docker. It was mainly based around the machine/host paradigm. If we wanted a service (Redis for example) to have a constant endpoint we could:

-

Set a constant IP address to that instance. If that instance fails we just launch another instance with the same IP address. Almost all cloud providers have such solutions today (Elastic IPs on AWS for example). This solution is not relevant in Docker days since a single IP or machine can serve a lot of different components.

-

Use en external Service Discovery solution like Consul. Each machine runs an agent and there’s a Consul server which holds the state of each service and its endpoints. Service discovery is done via DNS resolve for each service. There are adaptations of this method to work with Docker but it requires a significant amount of setup to work flawlessly.

-

Use a Load Balancer with a constant hostname or IP for each service and put all relevant machines which run the service behind it. Each machine which is started registers itself to the appropriate Load Balancer. An example for this is AWS’s Auto Scaling Groups which work exactly this way.

As we see the old problem of Service Discovery already has some well known solution but none of them work out of the box with Docker. AWS Auto Scaling Groups deals with VMs and not Docker containers while Consul can work with Docker but it really feels like it was not designed this way in the first place.

Today’s Docker orchestration tools are usually bundled with some abilities of Service Discovery.

High Availability

HA and redundancy, like Service Discovery, is also a problem which existed before the Docker era. For example, AWS Auto Scaling Groups make sure you have at least X machines up and running with a certain service. It can even adjust the number of running machines dynamically via API or pre-defined rules.

While this problem was solved for the machine-based paradigm, Docker make keeping HA and redundancy a little bit more interesting: We scale by running more Docker containers, not by starting more machines. We can scale a certain service up using the same pool of resources we already have. It means that our service scaling is detached from our cluster resources scaling and scaling up or down does not necessarily imply adjusting the amount of resources we require. We have to scale services and resources separately.

Some of today’s Docker orchestration tools have some basic features of container horizontal scaling. Scaling the cluster – adjusting the amount of resources available to the orchestrator – is done separate of container management.

Resource Management

In the days before Docker we were launching new service instances by launching new machines. We had some kind of mapping from each service to its CPU/memory requirements so we knew exactly what type of machine we need to launch.

With Docker this is not the case: We have to schedule our containers into an existing set of machines. Our resource pool is more or less static and the orchestration tool needs to fit the set of containers into the set of machines in an optmizied manner. It sounds like a simple optimization problem but it really isn’t because the set of containers changes dynamically at any given time. We need to balance between spreading our containers equally and leaving enough resources in case we want to start a container which requires a large mount of resources.

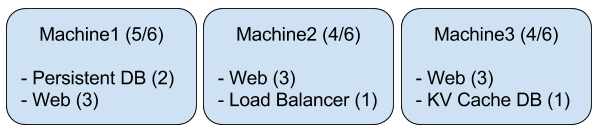

Let’s take the infra from Diagram II as an example. Assuming this is the table of resources required by each service:

Web – 3

Load Balancer – 1

Persistent DB – 2

KV DB – 1

Each of the 3 machines has exactly the same resource capacity of 6. We have at least two obvious ways to layout these containers:

-

Sparse Layout – This is the exact same layout as Diagram II shows:

Diagram III – Sparse Layout In parenthesis we see each machine resources usage.

This layout looks pretty good – all of the containers are spread between our instances and we do not “choke” a single instance – each of them has spare resources. But this setup also bears a problem with it: what if we want to scale our web service up to 4 instances? We don’t have a single instance with at least 3 resources free. So maybe this isn’t the best layout for our containers? -

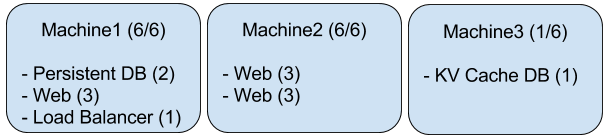

This would be another way to arrange our containers:

Diagram IV – Dense Layout Now machine 1 and 2 are full – they have no spare resources at all. That leaves machine 3 pretty free to run each of our services when needed. But is it even possible to layout our containers this way? Can you spot the problem here?

Ports of course. On machine 2 we have two web instances which require the same port. Does that mean we can’t schedule two web containers into the same machine? This problem takes us directly to our next section, port management.

Ports Management

No matter how you twist it, the same port cannot be occupied by two different processes on a given machine. When you know which services are going to run on a machine before-hand, you just have to make sure not to create port collisions. With Docker infrastructure you don’t have this luxury of course – services replace machines and get re-scheduled all the time.

Docker orchestration frameworks usually take one of the two standpoints: The first one is to avoid cases in which containers that require the same port on the host machine will be scheduled to the same machine. This is an easy solution to the problem but as we saw it may imply really tight constraints on the way we can layout our containers. It can get to a really nasty situation in which the orchestrator cannot schedule a container only because ports constraints.

The other way orchestration frameworks deal with port collisions is by assigning a designated random port for each of the containers in a machine and route traffic inside by themselves. If we take machine 2 in Diagram IV as an example, it means that each of the web services has a port opened on the machine itself which routes directly to the web service instance. Port 3000 on the host machine will lead to the first web service and port 3001 will lead to the second.

Summary

As we saw, we already did orchestration before Docker, but instead of orchestrating containers we were orchestrating virtual machines. Some of the problems in the orchestration world, live Service Discovery and High Availability, already had solutions which were just needed to be adjusted to work with containers. Some of the problems, like Resource Management and Port Management, were completely new when Docker arrived and required some creative solutions.

So what does an orchestrator do? It schedules our containers into a cluster of machines in an optimized manner while keeping high availability and has a basic support for service discovery. The orchestration framework we choose will set the way we manage our cluster and the way we do operations. Is is essentially the core operations tool we build everything around.

There are various orchestration frameworks around: AWS ECS, Kubernetes, some native Docker solutions and more.

In the next post we’re going to have a deeper look at ECS and Kubernetes and try to understand why we at nanit.com went with the latter.

Thanks for your docker write up, very informative & helpful

Interesting setup. I definitely learnt a lot from reading your post. So, thank you for that.

As someone who has never used docker in production, I have a few question though.

Is there any advantage of running the web server containers in several machine, instead of running it in a single machine with more resource dedicated to it? It seems like you’re paying for the cost of the maintaining the cluster anyway, why not use as much resource as possible?

A pretty common setup is having AWS EC2 instances behind ELB, and then start/terminate instances according to load as needed in order to save cost (same thing with DB/workers, etc). Is your setup meant to solve an entirely different problem? Because I’m having trouble seeing the parallel.

Hi hdnr these are some really good questions I will try to provide some answers:

The advantages of switching to Docker containers are numerous:

They provide isolation, portability, quick boot times, consistency, application + dependencies in one package and a lot more. It totally refines development-production similarity when working on a software system. The same container that runs on the developer’s machine will run in production. When working with Docker, your delivery pipeline is a lot more consistent and reflects better the code that runs on production later on. Docker has all the advantages VMs have, but with some major improvements: they are a lot more lightweight both on boot time and when moving them over the network, they share host machine resources and more. A quick search in Google will yield more than you can read about this topic 🙂

You can still have your cluster VMs on an AWS Auto Scaling Group and add/remove machines as needed.

I agree managing Docker containers is more difficult than managing VMs, but I don’t think of Docker mainly as a new way to run things on production, this is just the side-effect for me. I think of Docker as a better, more consistent, way to develop and deliver software projects. Once you get through the first barrier of setting up a cluster and choosing an orchestration framework, you start to enjoy the major benefits Docker provides.

Did not see any mention on gateways. Did you look at them, like AWS API Gateway or the open-source Kong (https://getkong.org) to efficiently manage your microservices?

AFAIK AWS API Gateway is specifically designed to deal with HTTP based APIs.

Docker solves a problem that is far broader and generic than this and it is not cloud-provider specific so I don’t think of it as a comparable tool.

I really wasn’t aware of Kong and I will definitely check it out, it looks very interesting.

it will be very useful once the LB support is out. https://github.com/Mashape/kong/issues/157

Also good article here: https://medium.com/on-docker/docker-networks-discovering-services-on-an-overlay-66c8906ffd49#.bx5qn6iru